Sky Views: Monuments are symbols of the past and present

Saturday 19 August 2017 02:53, UK

Lewis Goodall, Political Correspondent

"The past...", William Faulkner, the gothic writer said, "... is never dead, it's not even past".

How right he was. And it was in his native South where that fundamental truth was illuminated for all to see again this week, at times quite literally.

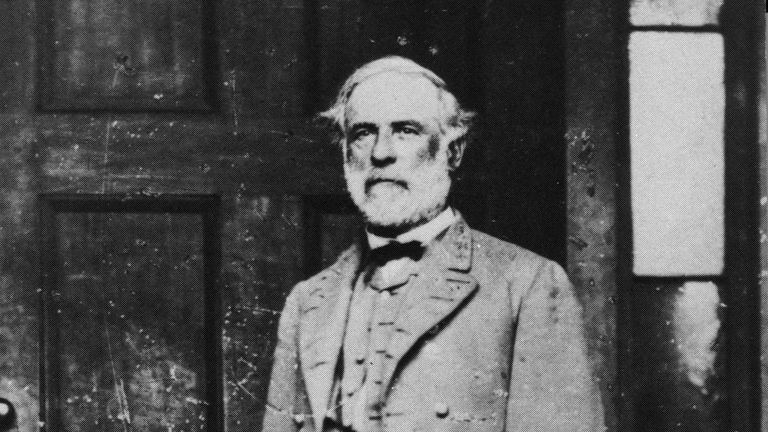

On Sunday we saw the ghostly spectre of hundreds of white supremacists and neo-Nazis march down the streets in Charlottesville, Virginia, a flame in each hand. All, ostensibly, because of the proposed removal of a statue of a man who died when Queen Victoria was in middle age almost 150 years ago.

There are two questions here:

Why has the status of our public monuments come to such a head of late?

And what should we do about controversial statues in public spaces?

The first, I think, is easier to answer.

Over the last few years, across Britain and the United States, issues of culture and identity have come to dominate our politics.

The right and especially the left have moved from being anchored in economic issues, as they had been in the 20th century, to become increasingly preoccupied with social and cultural ones.

It's interesting that in 2009, when the Democrats controlled both Congress and the presidency, no attempt was made to remove Confederate statues in the Capitol building.

Today, however, the Democratic leadership are demanding such action is taken immediately.

Clearly there has been a cultural shift in a relatively short length of time.

This has been sent into overdrive by the election of President Trump who, I think uniquely in the pantheon of his presidential predecessors, seems determined to be an overt partisan of one of the sides of the culture war.

But this isn't just confined to America.

Whether it's Cecil Rhodes, Edward Colston or Oliver Cromwell, there has been a series of concerted attempts to remove certain public memorials and monuments of historical figures.

I think it is probably the endgame of a more fragmented, multicultural society which we have become over recent years. In the past, history was simple.

There was one history in each country which was written by the dominant group, which, throughout virtually all Western history, was white men.

Even if competing histories did exist they were not allowed oxygen, they were given no imprimatur of state approval.

Today, however, no single group holds such ideological hegemony, so questions over symbols and culture are more fiercely contested.

We need to reckon with our own histories and, when there's no agreed narrative, it's more important than ever to have some method to find a way forward.

There are several competing priorities here.

On one hand, we don't want our historical monuments to be rewritten every generation. That would demean our past and leave open the accusation by malign forces that elites are trying to "rewrite history", as Nigel Farage suggested a few days ago.

We also have to be humble and say that we as a generation are not the end point of human society. We don't have a greater access to objective virtue any more than previous generations did or future generations will. Society's mores and versions of history mutate, wax and wane as the years go by. A titan of one generation can look like a monster to the next, and vice versa.

But there has to be enough flexibility in the system to account for societal shifts too.

Is anyone saying it was wrong for the Russians, with the bloodlust of revolution ringing in their ears, to remove statues of Marx, Lenin and Stalin and to unceremoniously dump them outside the Tretyakov gallery in Moscow in 1991 as the Soviet Union crumbled?

Or that the citizens of Baghdad were wrong to pull down and smash the statue of Saddam Hussein as his regime fell in 2003?

Or if a statue of Hitler existed now in a park in Berlin, that it would not be an affront to Jews and members of the human race everywhere?

It cannot be satisfactory to simply say it's part of history ergo we should leave it where it is without question. History is a living thing. What and who we honour says something about us.

But, whisper it, does Trump have a point? He says "the left" will be coming for George Washington or Thomas Jefferson next.

One thing he might mean is: Which of our heroes can live up to our exacting standards?

Charles Darwin was a great biologist but he was no feminist. Indeed he argued that women's brains were "analogous to those of animals". Today he'd be considered to have a brain analogous to a dinosaur and kicked out of the Royal Academy.

And what about Jefferson? He would be considered the worst kind of racist and xenophobe - he wouldn't have been out of place on that white supremacist and Nazi march just a few days ago. He thought it best that people of colour were transported to Africa and that they were inherently suited to be slaves.

But should we remove a statue of Darwin or Jefferson? This brings us to the second point. It seems to me, no. And that's as a result of the application of two criteria:

1: Were the views or actions we now find objectionable ubiquitous and near universally shared by their contemporaries?

2: Do they have other major contributions? Are they known for something separate to the issue at hand?

So to take Jefferson as an example again: His views were by no means unusual for his time, indeed they were commonplace. However, there were some people who weren't slave owners and argued for emancipation. He gets a halfway pass.

But his contributions were truly enormous in other regards. He wrote the Declaration of Independence, he was the country's third president, a founding father, philosopher king and intellectual behemoth. It would seem peculiar for the United States not to have a statue of him in a public place.

As for Darwin, though a sexist, he cannot be said to be uncommon for his time in that regard and was not principally known as an anti-feminist or anti-suffrage campaigner.

However, his status as father of modern biology must make him worthy of public merit.

General Lee, by contrast would fail both measures. His views on slavery, whilst shared by some, were rejected by many in the North and South, indeed so much so that a war was fought over the issue and it seems to me a push to argue any other achievement of his can overshadow his role in the Confederacy.

These criteria aren't foolproof. There will be many borderline cases and it is no sure path to objectivity. But it is a start.

And in any case, statues don't have to be burned or destroyed, they can be taken to museums, displayed as exhibits, or abandoned outside galleries. Perhaps every nation needs its own Tretyakov.

After all, public display implies honour, that a society thinks you are worthy of recognition. That is why it must be so galling for African-Americans to see a man like Lee honoured - a man who, had he had his way, would still have many of them in chains today.

And as for the borderliners, perhaps we need to recognise our contested narratives by having more statues and memorials full stop. Instead of honouring the same old men, many of whom with questionable views in one respect or another, let's have more statues of exceptional women, of working class heroes and of ethnic minority pioneers.

"The past is a foreign country...", L.P. Hartley said, "...they do things differently there". We should respect that.

But we're in control of the now.

And we shouldn't be afraid, occasionally and with forethought, to do things our own way, in the present.

History wouldn't respect us, if we didn't.

Sky Views is a series of comment pieces by Paste BN editors and correspondents, published every morning.

Previously on Sky Views: Sam Kiley - Cash not food is best for Somalia