Sky Views: Rohingya story must stay in focus

Wednesday 4 July 2018 00:47, UK

Tom Cheshire, Asia correspondent

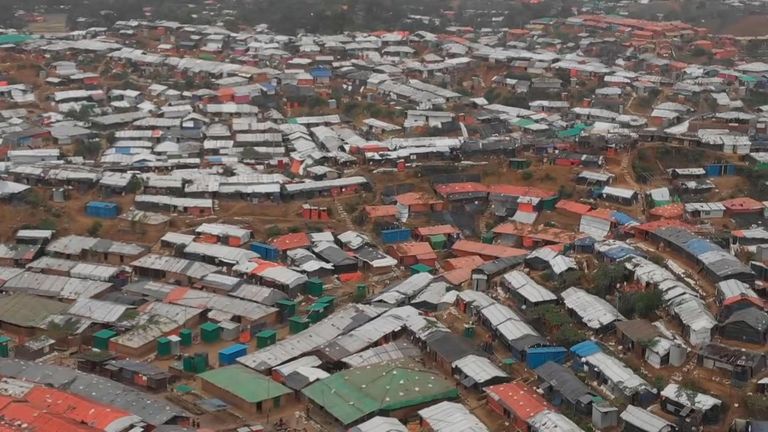

As we walked out of the Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh one day last week, our fixer gestured to the stalls selling food on the side of the road: "These are the rich Rohingya."

They were still shacks but they were bigger and more comfortable than the shelters occupied by those who have arrived since August, fleeing violence in Myanmar.

The reason those Rohingya are the "rich" ones, though, isn't something to envy. They have been in the camps since the early 1990s. Many children have lived their entire lives inside.

A similar fate seems inevitable for the 700,000 people who have arrived more recently. Although the UN and Myanmar agreed a deal in May for Rohingya to return home, conditions are nowhere near safe enough.

And even then refugees may not be able to relive the trauma of a return. One Rohingya woman who said she had been gang raped by soldiers told us: "I would never return there. I would rather be killed here than go back to Myanmar."

So now hundreds of thousands people find themselves in a dirty, muddy, dangerous limbo. As impressively welcoming as the Bangladesh government has been (can you imagine the British government - or public - welcoming in nearly a million refugees?), it is still keeping people in purgatory.

The Rohingya there are recognised as refugees but are not allowed freedom of movement, the right to work or the right to proper education.

They have to stay in the camps - and that's becoming less safe. Firstly, because of the monsoon rains, and the landslides, floods and disease they could bring.

Secondly, confinement brings discontent. That's useful for human traffickers, who find it easier to lure people into their networks with promises of a better life. It's also useful for radical elements inside the camps.

We were ordered to leave the camps at 5pm every day, that's when the Bangladesh military also left. That gives cover for gangs to meet, including the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (Asra), the insurgent group that killed several Burmese soldiers and police officers in 2016 and 2017.

Myanmar's brutally violent response came after that. Last month, a community leader who had criticised Asra was hacked to death after dark in the camps. People inside the camps we spoke to said they felt less safe now than they had a few months ago.

At the same time, there's the sense that international attention is drifting. Myanmar continues to deny it carried out ethnic cleansing - the tactic employed by regimes around the world to stonewall through attention, and hope people lose interest.

Western governments too have been wary of intervening too heavily. They want to preserve the fragile democracy headed by Aung San Suu Kyi, especially given the military's enduring dominance in Myanmar.

But there's an easy way to keep the story in focus. The International Criminal Court is reportedly building a case behind closed doors to investigate crimes against the Rohingya. It should be bold and public in prosecuting it - and in bringing the perpetrators to account.

It won't mean the Rohingya return to Mynamar any quicker. But it would give those living in the camps some justice, at least.

Sky Views is a series of comment pieces by Paste BN editors and correspondents, published every morning.

Previously on Sky Views: Paul Kelso, We must take another look at the NHS