Sky Views: Maps are changing our lives

Wednesday 6 September 2017 04:23, UK

Tom Cheshire, Technology Correspondent

There's a Lewis Carroll tale about a mysterious character who has a beard and a German accent. He's called Mein Herr and tells stories of his equally mysterious country; specifically, how they make maps.

The usual scale - six inches representing one mile - doesn't much impress Mein Herr. Where he's from, he boasts, they first created maps with six yards to the mile; then a hundred yards to the mile.

"And then came the grandest idea of all!" Herr says. "We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile."

Asked if the actual size map gets much use, Herr replies: "It has never been spread out, yet.

"The farmers objected, they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight."

Mein Herr's map is meant to be ridiculous and impossible. It's also now the stated aim of technology companies and governments around the world. We are entering a new, golden age of mapping. And these maps not only represent the physical world, but will start to reshape it.

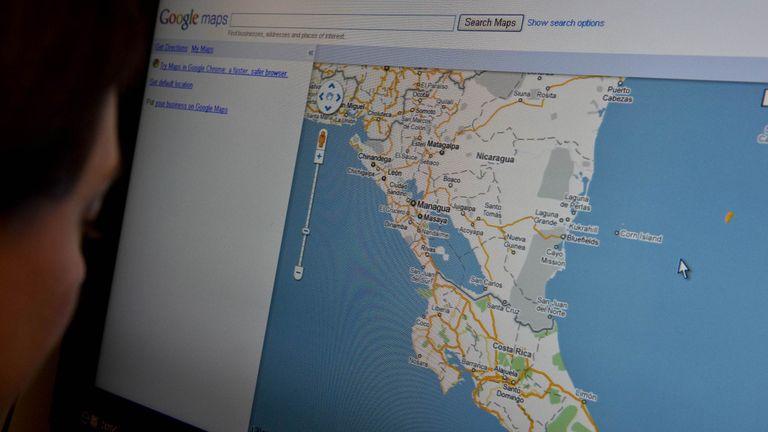

The first stage of this now seems pretty quaint. Google Maps and Google Earth both launched in 2005. (Google Earth has actually since expanded to Google Moon and Google Mars).

Other maps existed - heyo Yahoo Maps and Multimap - but Google took digital mapping mainstream. They added satellite imagery and then, even more ambitiously, Street View.

By 2012, its cars had driven five million miles - roughly 125 times the circumference of the planet - and its head said that Google was on a "never-ending quest for the perfect map".

But it was 2007 - when Google Maps appeared on the iPhone - that the mapping revolution began. Location is one of the most compelling sells for a smartphone. Businesses like Uber and Citymapper have been built on its combination of GPS and internet connectivity.

Those apps don't just provide a service to users, though; they provide ever more data to make the map ever more perfect.

Last week Uber released Uber Movement, a mapping tool for city planners that lets them see how Ubers - and by extension all traffic - moves around the city in real-time.

Citymapper, the journey-planning app, relies on open public data on things like train times and bus arrivals. But its own insight can then be used to improve bus routes.

Others are layering even more data on.

Facebook, in its inimitable creepy way, has now geographically mapped the Earth's entire human population, using data from satellites and government censuses. Earlier this month it said it had mapped the population of 23 countries to within 15ft.

Governments see the value too.

The Conservatives' manifesto pledged to "create the most comprehensive digital map of Britain to date", part of a plan to support the digital economy here.

The Ordnance Survey is already working on a 10cm resolution map and building a "digital twin" of Bournemouth, to accurately map potential 5G coverage.

In another fantasy map from literature, Italo Calvino imagined all the unknown and ephemeral routes of a city - the paths taken by furtive cats, say, or smugglers dragging kegs of gunpowder through alleys.

"A map of Esmeralda should include, marked in different coloured inks, all these routes, solid and liquid, evident and hidden," he wrote.

To look at the maps offered by Google, Uber and Citymapper is to see just that: familiar territory, loaded with layer upon layer of dynamic information.

The same is true of the ghostly yet colourful 3D maps developed for driverless cars. These pull in data from laser scanners (a technology itself giving rise to a whole new type of geospatial mapping), from radar, from computer vision, from pre-existing maps and from things like Uber's real-time traffic, and they will be vital in determining which companies thrive in autonomous vehicles. Maps are the competitive edge.

The next stage is entirely virtual. In 2016, Google Waymo's driverless car division logged three million miles on public roads. But Waymo has created AI-powered software called Carcraft - a representation of real and imagined worlds - to expand its testing.

In this virtual map, it has 25,000 driverless vehicles driving through digital reproductions of California and Texas - and they logged 2.5 billion virtual miles in 2016.

That virtual testing is downloaded back into the physical cars, which then feed their data back to the map, making it - and themselves - more perfect still.

The map is indeed now the territory: for the car's software, reality and simulation are both equally useful in learning how to drive.

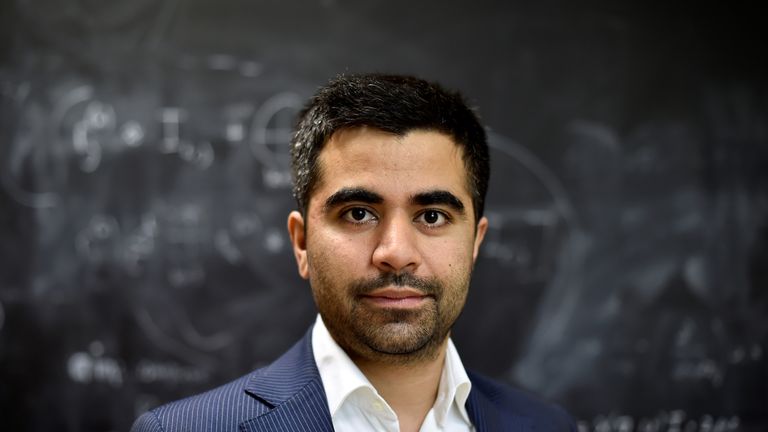

Or take London's most high-profile current start up - Improbable, which took $502m in investment earlier this year. Its tagline is "Create new worlds" and its founder, Herman Narula, says he wants to create "genuine, living, breathing recreations" of reality.

Improbable's simulation of the city of Cambridge includes 130,000 inhabitants, traffic and public transport, along with internet, phone and utility lines.

Narula hopes his simulation software - his maps - will be used to help understand biological systems like tumours, the housing market and violent extremism in populations.

Maps are becoming bewilderingly complex just as they become much more crucial to our future.

Mein Herr's map was never unfolded.

Instead, he says: "We now use the country itself as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well".

Lewis Carroll was writing in 1893.

The tech industry is making the absurd achievable.

Sky Views is a series of comment pieces by Paste BN editors and correspondents, published every morning.

Previously on Sky Views: Katie Stallard - Military action in North Korea is risky